The UrOnline Project

Ur was one of the first cities in human history. As such, it is incredibly important not only to archaeologists and historians, but to people all over our modern urbanized world. Fabled as the city of the Sumerian moon god Nanna and the home of the biblical patriarch Abraham, Ur witnessed thousands of years of human activity. Once supplied with water by by the Euphrates, it was eventually abandoned because the river meandered too far away. It now sits some 6 miles southwest of the Euphrates in southern Iraq. The excavations at Ur (now Tell al-Muqayyar) remain key to much of our understanding of the ancient Near East.

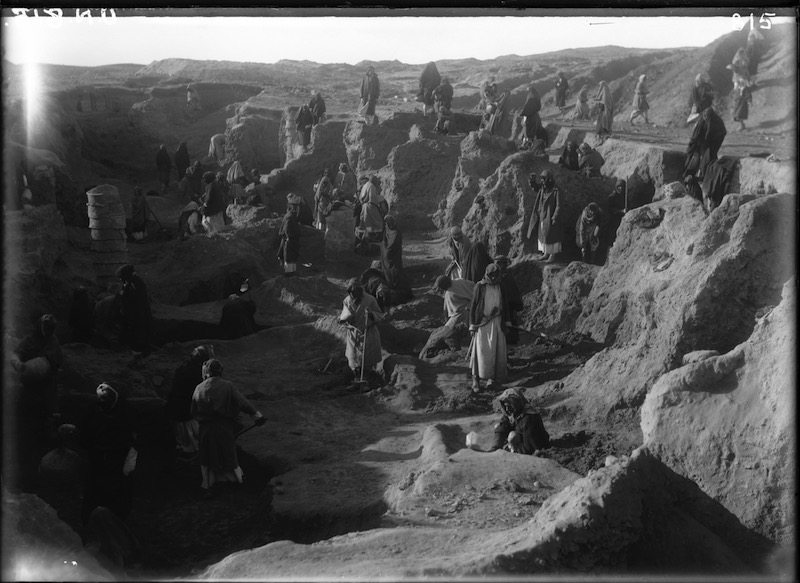

The site of Ur has fascinated modern travelers and archaeologists since the 17th century, but no extended excavations occurred until the early 20th century. In the wake of World War I, the British Museum and Penn Museum formed a partnership to excavate at Ur under the direction of Charles Leonard Woolley. Ur was the first archaeological site to be excavated under a permit from the Department of Antiquities of the new nation of Iraq. That permit agreed that half of the artifacts recovered would go to the future Iraq National Museum, and the other half would be divided between London and Philadelphia.

Woolley's excavations at Ur yielded tens of thousands of artifacts, photographs, letters, reports, and other documents which today remain divided among the three museums. When the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad was looted in 2003 it raised alarms over preserving important cultural heritage, and prompted the British Museum and the Penn Museum to investigate their own holdings from Ur in an effort to assist the Iraq National Museum to determine what was missing from their collection. This investigation showed that records at both museums were incomplete; the looting showed that artifacts and records could be lost at any time to theft, environmental damage, or being misplaced. And it was also a reminder that artifacts and records from one site were divided across the globe.

Now the two museums are making sure their records are complete and up to date. Ur was well published for its day, but there is still an enormous amount of data that is unpublished—letters from the field, notes, original photos, as well as information on thousands of artifacts. And all of this information should be public, to expand knowledge of the ancient Near East and to make research into the site easier and more efficient.

This project digitally reunites these artifacts and their records in one virtual place, preserving them and making them widely available. This increases the number of visitors and researchers who can engage with them but also means that they remain separate when they were originally together at the same site. Digital technology has advanced enough to make archaeological data accessible and linked, and to preserve it for the future.

Through the generosity of the Leon Levy Foundation, lead underwriter, the Kowalski Family Foundation and the Hagop Kevorkian Fund, UrOnline preserves digitally and invites in-depth exploration of the finds and records from this remarkable site.